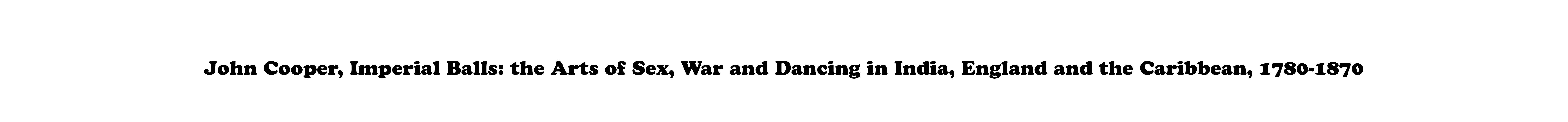

fig. 21 Francis Frith &co., ‘3191, Cashmere: Nautch Girl (dancing attitude)’ (c.1850-60), whole-plate albumen print from wet collodion glass negative, 16.5 x 20.3 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

fig. 23 Now unknown Indian artist, Shiva Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance (twelfth century), made in Tamil Nadu, cire perdu cast bronze, 85.2 x 75 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

fig. 24 Frontispiece to Ananda Coomaraswamy, The Dance of Siva (New York, 1924) showing photograph of ‘Cosmic Dance of Nataraja. Brahmanical Bronze. South India. 12th Century, Madras Museum’

In this dancer’s dancing remains also the pre-colonial Hindu image of Siva Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance (fig. 23). This image of Siva is widely known from the 12th Century onward, especially in Southern India. This aspect of Siva is particularly associated with Cidambaram, the temple complex in Tamil Nadu devoted to Siva Nataraja, a key site in mythological narratives of the origin of dancing in India. Also at Cidambaram are sculpted on the four gopurams, or gateways, relief panels depicting the 108 karanas (poses) described by Bharata in the foundational treatise on Indian dancing, the Natyasastra. This treatise and the sculpture at Cidambaram together formed primary documents in the restoration of classical dance traditions in the 1930s which has continued to define the Indian dance world until the present day. I am therefore looking at this mid-nineteenth century photograph of a dancer next to Siva as already a postcolonial image because the dancing subject contests the imperial stillness of the photographic medium.

This (fig. 24) is the image of Siva Nataraja printed at the front of Ananda Coomaraswamy’s 1926 volume The Dance of Siva. In this position Siva stands like a potent threshold figure to a work of cultural nationalism, heralding Siva’s threefold historical work as creator, preserver and destroyer of all that is. In the essay on 'Siva the Lord of the Dance' from this collection Coomaraswamy crafts the signification of the Siva motif with descriptions from Sanskrit literature. He quotes Tirumula’s Tirumantram: ‘The dancing foot, the sound of the tinkling bells, / The songs that are sung and the varying steps, / The form assumed by our Dancing Gurupara— / Find out these within yourself, then shall your fetters fall away’ (The Dance of Siva, 61). ‘Siva is a destroyer and loves the burning ground’, writes Coomaraswamy below, the burning ground being the crematorium, ‘But what does he destroy? Not merely the heavens and earth at the close of a world cycle, but the fetters that bind each separate soul. Where and what is the burning ground? It is not the place where our earthly bodies are cremated, but the hearts of His lovers, laid waste and desolate’ (ibid.).

Could it be that the floor (fig. 21) underneath the nautch girl’s feet, as much as the valley (fig. 22) of the Kashmir, was a burning ground like Coomaraswamy describes, an ash-coloured place where the world cycles of creation, preservation and destruction of the 1850s were closing under the dancer’s feet?