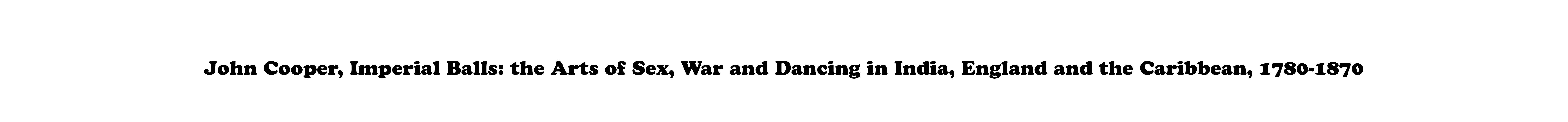

fig. 21 Francis Frith &co., ‘3191, Cashmere: Nautch Girl (dancing attitude)’ (c.1850-60), whole-plate albumen print from wet collodion glass negative, 16.5 x 20.3 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

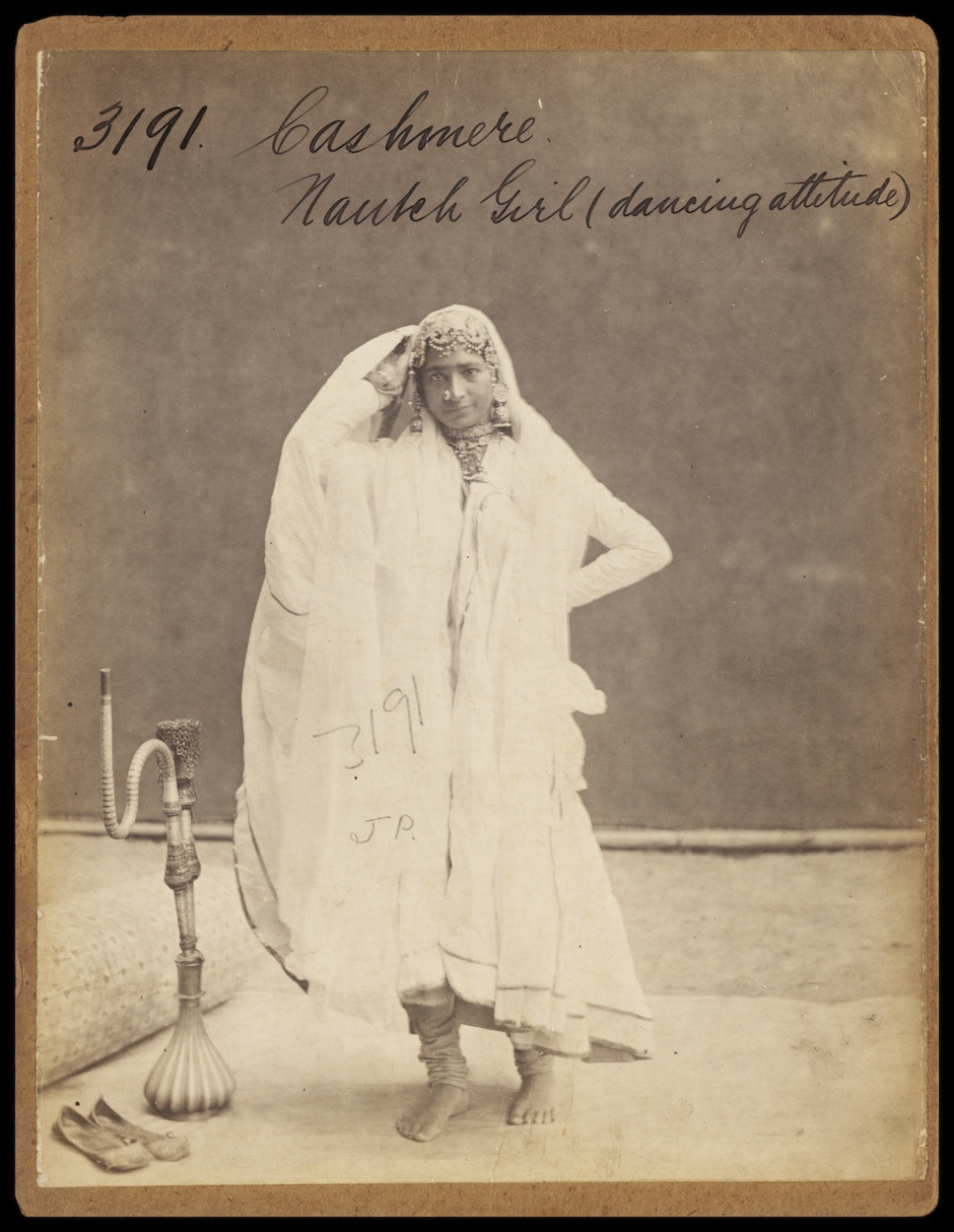

fig. 22 Francis Frith &co., ‘3203, Cashmere: The Scinde Valley above Sonamarg’ (c.1850-60), whole-plate albumen print from wet collodion glass negative, 16.5 x 20.3 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the history of colonialism there is a connection between representations of the body and representations of land. Dance makes this connection particularly visible. These (figs. 21 and 22) are two images of Kashmir. The two whole-plate albumen prints were part of the Universal Series made by Francis Frith &co., one of the largest commercial photographic practices in the UK during the 1850s, 60s and 70s, a time when production costs were being driven down and the postcard format was making mass international circulation possible. There are over 4000 images in the Universal Series from Egypt, Japan, Andalusia, China and India. For the most part these works consist of landscapes, topographical views, historic sites and city monuments. Only a very few depict figures.

These photographs were taken at a time when the territory of Kashmir had been the site of fraught struggle between warring factions. In 1819 the Maharaja of the Sikh empire Ranjit Singh took Kashmir from the Afghans. Six years after Singh’s death in 1839 the first Anglo-Sikh War broke out, concluding in 1846 with the Treaty of Lahore which ceded Kashmir to the British EIC as an indemnity of war. Kashmir was then further embroiled in the struggle for succession between Shere Singh, Dost Muhammed and the EIC in the Second Anglo-Sikh war which concluded in 1849. After the uprisings of 1857 the Punjab as a whole entered a period of suzerainty, or indirect rule, by Britain.

The image of the dancer and the image of the landscape are similar. Both are composed by a diagonal structure, the first by an archetypal nautch stance, the second by the winding sections of the valley. Both display contrasting areas of light—the sky and water, the white cloth—and expanses of darker volume with detailed passages—the wooded slopes or pebbled river bed and the dancer’s jewelry. These are the effects the medium captures well. The values of these images are produced by their composition and detail and, ultimately, by their compliance to the governing equipment of the photographic apparatus. The Universal Series extends a form of indirect rule over the dancer and the landscape, a suzerain power which displays the territory of the land and the dancer as indemnities of imperialism.

But because this is a dancer dancing we can see genealogies at work in her presence other than indemnity.