Dancers of the early nineteenth century were, I think, a special kind of subject. This is partly because they so frequently carried and exchanged signs of national sovereignty whilst they danced. They were like clothes horses of imperial identities. Even though a dancer like Marie Taglioni was and has been since called upon to be an emblem of the aetherial aesthetics of the Sylph and the classic white ballet, the geography of the dance market in the 1830s and 40s required dancers to possess a multi-lingual grasp of choreographic idioms. Here (fig. 16) she is pictured as a sylph, elsewhere (fig. 15) as an Indian, in other prints a gipsy, in others a Spanish or Neapolitan dancing girl. In this left most print made in New York after a European original, Taglioni is flanked by Carlotta Grisi and Fanny Elssler clothed in Grecian and Spanish garb respectively. That such alliances of nations were exchanged in the practice of ballet and that they were eroticized in and by means of this exchange is stated, I think, in the extreme delicacy of touch between the dancers’ hands. What could this manual poignancy signify? In light of the above readings of Pas de Quatre and Pas de Déesses and The God and the Bayadère, I see in these interlacing hands both an image of the gracefulness which erupted at the contact between symbols of colonized lands and a displaced image of the impresario’s contractual dexterity.

Perhaps because she was the only one of these three dancers actually to have traversed the space the image reproduces, Fanny Elssler is the most emphatically present of the three dancers here (fig. 16). In 1841 Elssler commenced the first of her two transatlantic tours, performing to acclaim in Havana, Washington and New York. Elssler is dancing the cachucha from The Devil on Two Sticks. She wears an off-the-shoulder pointed bodice trimmed with yellow gold and black lace. ‘The calf length tiered skirt has a pleated top tier trimmed with a deep flounce of black lace held by ‘gold’ ribbon. Her stockings are patterned and her hair is centrally parted and pulled back into a ‘coronet’ trimmed with a knot of flowers’ (V&A catalogue record). The thickness of decoration on Elssler’s black and yellow body signifies the entangled history of the ‘Spanish’ dance form she, an Austrian, exemplified to American audiences.

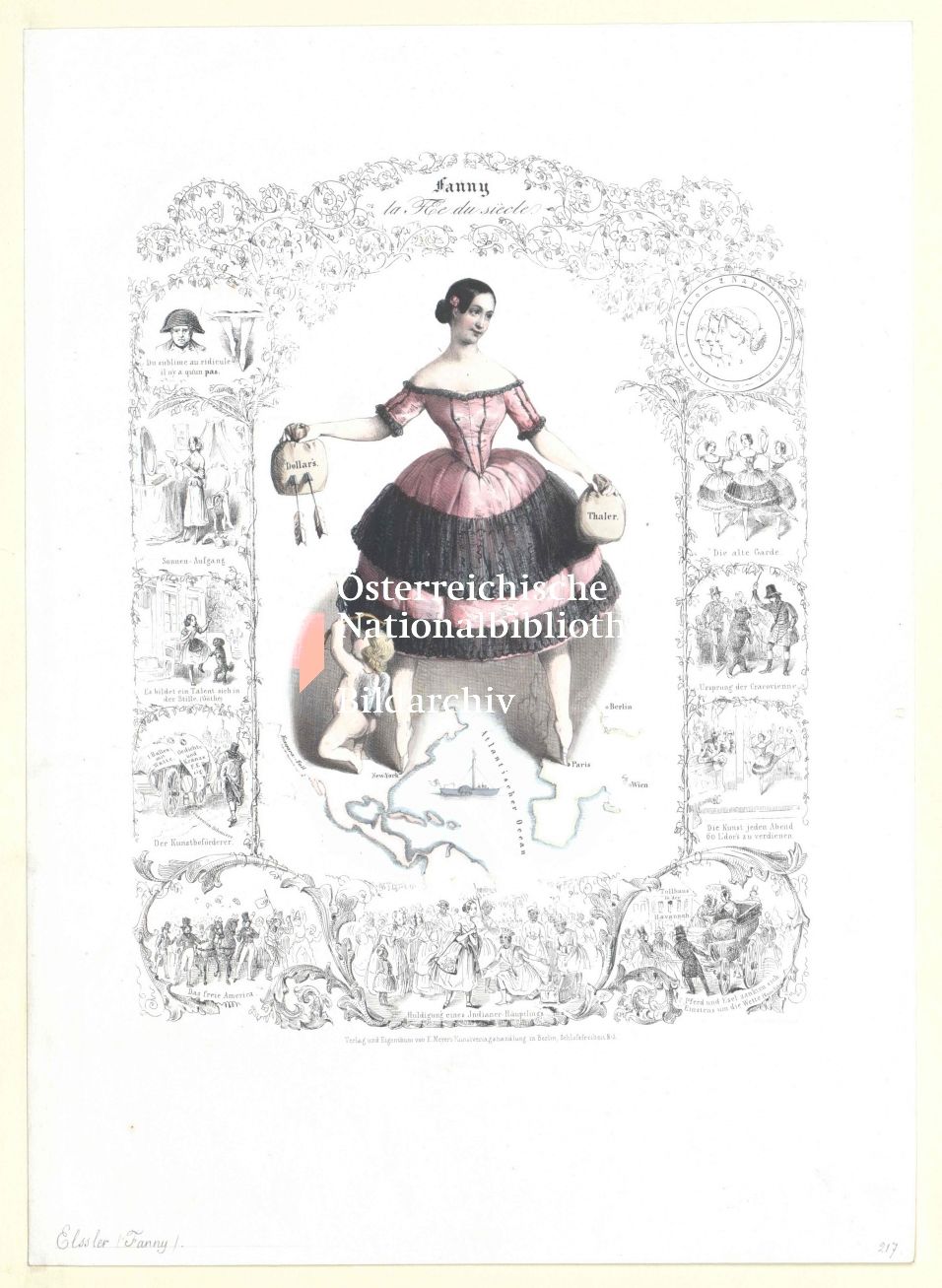

One of the things that ballet dancing performed on dancers was the exaggeration, inflation and extension of some parts of the body and the radical contraction of others (fig. 17). In 1840 Fanny Elssler embarked upon a tour of the Caribbean and North America. In this souvenir print she is shown dressed for the Spanish cachucha dance holding bags of dollars and thalers which a kneeling putto (possibly a sublimated image of her American impresario Henry Wikoff) penetrates with his bow and arrow. Her compass-point-like feet cross the globe in an elevated, circum-Atlantic second position.

This (fig. 18) is a picture of Caroline Augusta Joséphine Thérèse Fuchs Comtesse de Saint-James (1806-1901) in an equally Atlantic-sized Spanish bustle. The extremity of her port de bras or carriage of the arms is punctuated by the castanets she is shown holding and this poise is mirrored in the deft and wide sweep of her footwork which seems designed to maneuver the inflated shell of her dress in its fullest aspect. In her dancing career Madame Augusta toured performances of the cachucha, as well as the Neapolitan dance the tarantella around Europe, to New York, Cuba and throughout South America.

The cachucha for which Elssler and Augusta were famous was one of a number of Spanish dances which were popular in the 1830s and 40s. In The Code of Terpsichore translated into English and published in London in 1830, the Italian ballet master Carlo Blasis stated that ‘almost every Spanish dance, such as the Bolero, the Cachucha, the Seguidillas, of Moorish origin, are imitations of the African Fandango or Chica. They are therefore all marked with that voluptuousness, I might even say obscenity, which characterized their model’ (The Code of Terpsichore, 17).

A large number of colonial-romantic ballet prints were made of Spanish dancers in the 1830s and 40s. What were the hallmarks of the fashionable Spanish aesthetic? Geography mounted on the body as an inflation of its normal size. Black, yellow and red fabrics. Castanets. Darkness and voluptuousness. Associations with the ‘southern’. Genealogical links with ‘Moors’ and Africa. The voluptuous aesthetic of Spanish dancing in the first half of the nineteenth century was a product of the colonial world map, Spain being Britain’s voluptuous, Catholic, colonial, other and it materialized on the extruded contours and high affect colours of cachucha dancers’ bodies.