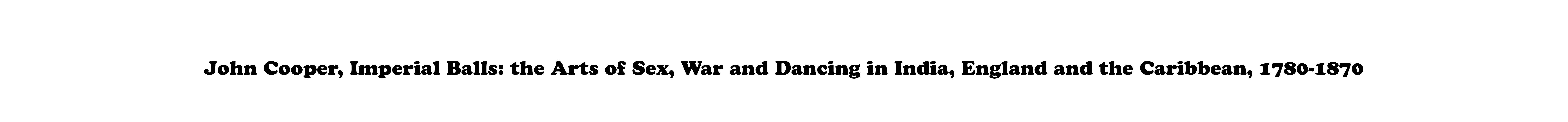

fig. 14 After Alfred Edward Chalon, Taglioni, published on frontispiece to The Exquisite, no.12 (1842-4), published by H. Smith [William Dugdale], London, British Library, London

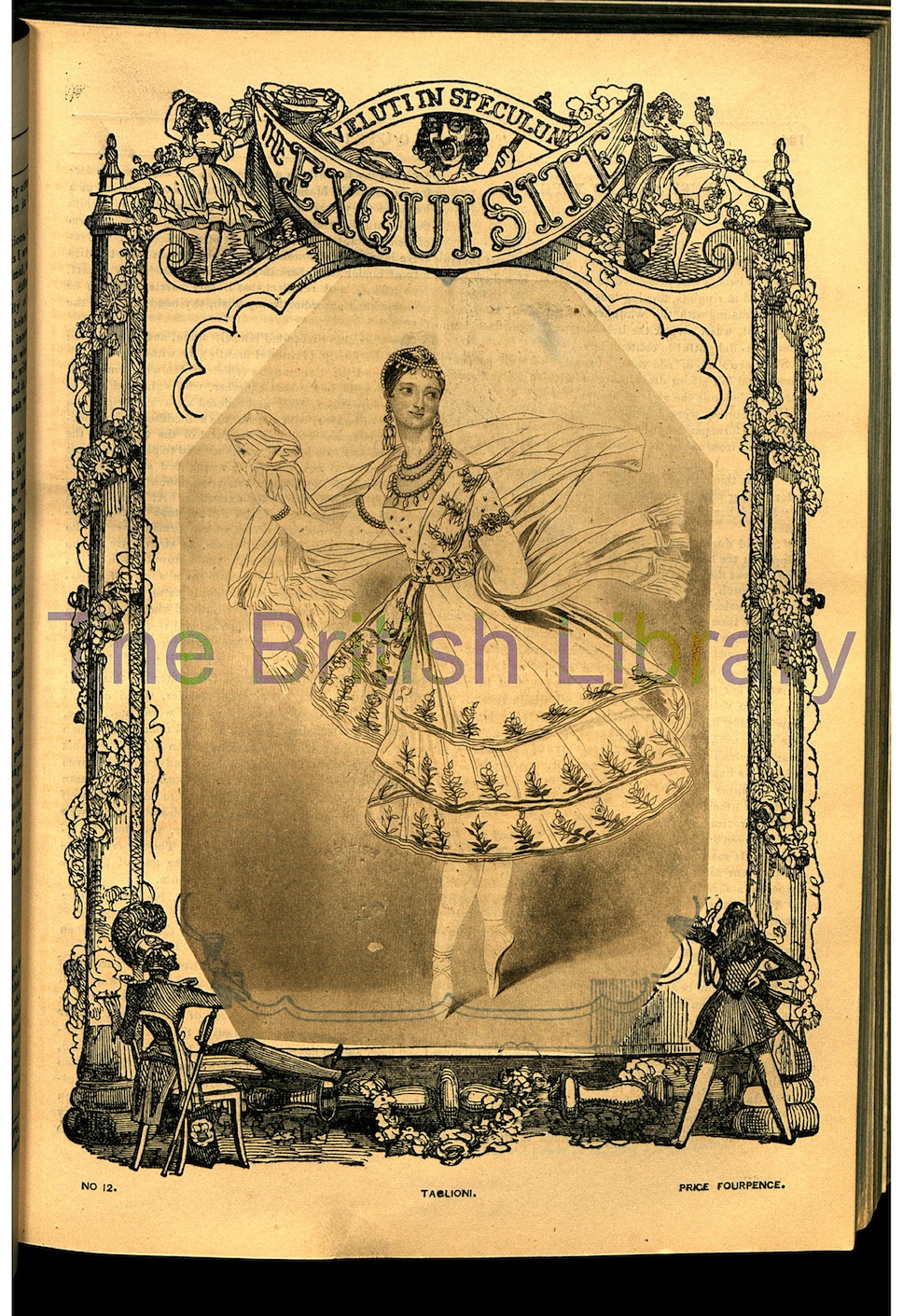

fig. 15 Alfred Edward Chalon (artist) and Richard James Lane (lithographer), La Bayadère - Portrait of Mademoiselle Taglioni (c.1830), printed by Graf & Soret, published by Ackermann & Co. and Rittner & Goupil, London, hand colored lithograph, 57.4 x 38.4 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This (fig. 14) is a picture of Marie Taglioni in the role of Zoloe the slave girl in the ballet The God and the Bayadère mounted on the front cover of The Exquisite. The Exquisite was a magazine of ‘amatory adventures’ published between 1842 and 1844 by the radical printer and agitator William Dugdale under the pseudonym H. Smith from premises on London’s notorious Holywell Street. The magazine frequently featured stories of whipping and chastisement and appealed to the military fops and civilian dandies pictured on its title page. The orientalized proscenium of the frontispiece bears the same Latin motto as Covent Garden Opera House: veluti in speculum (as seen in a mirror) surrounded by two high-kicking dancers and is adorned with pirated prints of ballerinas on the first thirty issues of the magazine.

Between 1786 when Gillray made ‘A Sale of English Beauties’ and 1830 when Edward Alfred Chalon produced this lithograph of the greatest ballerina of the colonial-romantic era, there was maintained an erotic connection between foreign nations, dancing, flagellation and the stage. This (fig. 15) is the hand coloured lithograph from which the Exquisite pirate is taken. The print’s deep wash of indigo foregrounds the whiteness of Taglioni’s stage pearl-drops, short-sleeved bodice, tiered dress, white maillot and ivory hands. Her hands and feet are as finely wrought as a piece of stage jewelry. The ornamental details of feet, hands, dress and accoutrements in prints of the ballet are important because it is in these extremities of surface and figure that the dancer’s image is defined. Here Taglioni is modeling two different roles simultaneously. She is at once a bayadère, a Hindu temple dancer or a dancing slave girl bedecked with superficial effects recognizable to Europeans as signifying an Indian woman and also the most classical of classical white European ballet dancers elevated en pointe in an attitude of ease and grace. The elevation rising out of her pointed feet in this print and the look of effortless grace and disalienated ease with which Chalon has rendered her hands and face describe a subject who is free from the heaviness of identities and indeed one whose special grace is to pass between them as the seasons of the theatres require and to maintain all the while a spectacular wholeness of body among the divisions of signs that surround it.