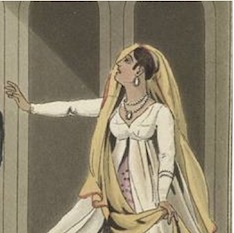

fig. 1 Mrs. Belnos, ‘Three Dancing Girls of Hindoostan’ from Twenty-four plates illustrative of Hindoo and European manners in Bengal (London,1832), hand coloured engraving, Yale Center for British Art

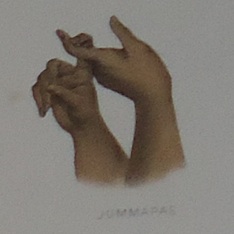

fig. 2 Exegesis of fig. 1 by Chetna Jalan at Padatik dance studios, Kolkata, September 2013

This plate shows three dancing figures from a nautch. The figures—who could be one or three dancers*—wear heavy salwar kameez, or ghungra, gold jewelry and dupattas covering their heads. Each figure is furled with the folded cloth of the dupatta or kameez whilst striking an attitude characteristic of the north Indian dance tradition Kathak. The anatomy of the ethnographic-picturesque is fully on display here: isolated figures, characteristic gestures, brightly coloured textiles.

In fig. 2 Chetna Jalan interprets the leftmost figure.

Jalan's interpretation confirms the descriptive note attached to 'Three Dancing Girls of Hindoostan' which remarks upon the slowness of this gesture. Gestures have tempo. The tempo (lasya, in the Kathak lexicon) prolongs the duration of abhinaya, that quality of elaborate facial expressionism articulated by tala (rhythm) demonstrated by Jalan in fig. 2. It can be seen most especially in the prolonged phrase of head and eye articulation between Jalan’s liftings of the veil. Abhinaya is primarily a narrative quality, testifying to the experience of a subject in a story rather than exhibiting the formal moves of pure dance, or nrtta (Kothari, 1989, p. 107ff). 'Europeans', Belnos writes, 'who do not understand the meaning of each figure', and who are therefore not fully part of its narration, 'find their dance insipid and dull'. S. C. Belnos herself observed such gestures intently and the hands of the dancers holding cloth here are related to her studies of Brahminical hand gestures in Sundhya, or the daily prayers of the Brahims [sic] (fig. 6). In the performance of nautch the expressively prolonged gesture of the covering of the dupatta disclosed the phenomenon of a subaltern whose 'dull' figure, according to Belnos, the European did not understand. It presented a colonial problem of the meaning of figures. This elaborate problem of the presence of a figure is named by Jalan with the word 'shy'.

Shyness characterizes the look of covered figures who danced in the elite Anglo-Indian social sphere depicted throughout the Twenty four plates illustrative of Hindoo and European Manners in Bengal (1832). The gesture of the dupatta seems to have been addressed specifically to this mannered, late East India Company world, or to have been a poignant but unanalyzed site of representation given the frequency with which it occurs. In Costumes and Customs of Modern India (1813) the play of the 'dooputtah' is prominent in two nautches (figs. 7 and 8). The 'dooputtah, resembling a plaid in form and size, made of fine muslin, bordered with a broad band of silk, is thrown over the head, and falls negligently over the shoulders' (Williamson and D'Oyly, 1813; note to plate XIV)** and the shyness or 'grace with which this part of the dress is managed', the text continues, 'constitutes much of the dancer's merit'.

The shy figure in the Belnos print is 'of the Musselman sect' and a native of Delhi, Agra or another of the provinces of 'Hindoostan'. The dupatta helps modify their colour. 'Some of these girls are very young, beautiful', and, 'much fairer than the Bengallees [sic]'.*** The dupatta makes the figure lighter and their lightness—a motor as much as an epidermal phenomenon—accounts for their migration not only across the carpets of a drawing room in that colonial simulacrum, the ‘city of palaces’, Calcutta, but across the whole of the former Mughal and Maratha territory recently consolidated under the British Presidency as 'Hindoostan'.

It is, then, perhaps not only the dancer’s migration from the Upper Provinces to Bengal which is represented by the movements in this dance and the colour of her skin but also the whole territorial acquisition of Hindoostan. The possession of territory, like the representation of dance, is both incomplete and ephemeral.

*It is unclear whether Belnos has represented a single dancer performing three different figures or three different dancers entirely. The confusion suggests that during the performance of nautch Belnos and the implied audience fudged the distinction between, as it were, figures and figures- or subjectivities and dance steps. This ambiguous, undifferentiated repetition of figures frames the nature of colonial figuration per se and can be seen throughout the work of Belnos and D'Oyly.

**Belnos notes that the dancers' 'upper garments are of gauze or very fine muslin bordered with gold and silver ribbons very deep, their trowsers [sic] are of satin'

*** D'Oyly and Williamson too noted the 'wide distinction' existing between 'the dancing women of Bengal Proper, and those of the Upper Provinces'